Sacred Rhythm

Evensong, St John’s Cathedral, 21 May 2017

1.

For Thomas Cranmer, the author of the Book of Common Prayer in its first two versions, the abolition of the monasteries made possible a new vision of holiness: the holiness of the cloister would be diffused everywhere and among all. The parish church, with its cycle of daily Matins and Evensong, would open up sacred time to all; indeed, in these two services, Cranmer had condensed the seven Benedictine hours. It was a kind of democratisation of the holy. Likewise, the Calendar, with its seasons, and its feasts and fasts, would embed ordinary time in a sacred rhythm. Worship would be the cantus firmus of life—the bass note, as it were of life.

For Thomas Cranmer, the author of the Book of Common Prayer in its first two versions, the abolition of the monasteries made possible a new vision of holiness: the holiness of the cloister would be diffused everywhere and among all. The parish church, with its cycle of daily Matins and Evensong, would open up sacred time to all; indeed, in these two services, Cranmer had condensed the seven Benedictine hours. It was a kind of democratisation of the holy. Likewise, the Calendar, with its seasons, and its feasts and fasts, would embed ordinary time in a sacred rhythm. Worship would be the cantus firmus of life—the bass note, as it were of life.

Was there ever a more glorious vision? Alas, it didn’t work.

For if our present-day sage, Charles Taylor, is correct, reforms such as these opened the way to secularism. Taylor, in his monumental work A Secular Age attributes secularism in large part to that levelling impulse which did away with the vowed religious life. Puritan dreams that there might be some general conversion to holiness of life never eventuated and, slowly but surely, the sacred rhythms fell into disuse.

Time was more and more ordered to production. What happened to sacred time—the rhythm of rest, of recollection, of charity, of mercy, of reconciliation, of sharing, of community life?

There remained, says Taylor, only the “tick-tock of secular time.” We have commonly felt, since the nineteenth century, as if trapped in “an immanent frame”. “Our actions, goals, achievements, and the like, have a lack of weight, gravity, thickness, substance,” he says. “There is a deeper resonance which they lack, which we feel should be there” (p. 307). “Some people feel a terrible flatness in the everyday, and this experience has been identified particularly with commercial, industrial, or consumer society. They feel the emptiness of the repeated, accelerating cycle of desire and fulfillment, in consumer culture; the cardboard quality of bright supermarkets, or neat row housing in a clean suburb” (p. 309).

Like a score without a bass line, shrill and chaotic notes are sounding—and the tempo is always quickening. So much for secularism.

2.

What key might unlock this cultural situation?

If Taylor is right, one answer is to retrieve sacred rhythm.

Marking sacred time is one important aspect of discipleship. That is how we mark our citizenship of a new world, our citizenship of heaven. Christ has risen into the eternal Sabbath: and therefore we take on a new relationship to time. We walk to the beat of a different drum.

I wonder—how can we offer people a liberating way out of secular time? How can we help them to break out of the time that is ordered to production? Perhaps it will not be to ask them to come to Holy Communion every Sunday—at least, perhaps not to begin with. Maybe the best way into the Church is, actually, a different kind of practice altogether—not confessional, not preachy. Another way might, I think, be through keeping the feasts and fasts of the Church.

I wonder—how can we offer people a liberating way out of secular time? How can we help them to break out of the time that is ordered to production? Perhaps it will not be to ask them to come to Holy Communion every Sunday—at least, perhaps not to begin with. Maybe the best way into the Church is, actually, a different kind of practice altogether—not confessional, not preachy. Another way might, I think, be through keeping the feasts and fasts of the Church.

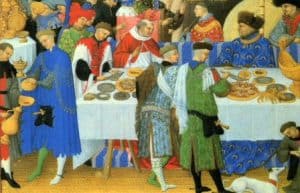

An unusual suggestion. But imagine: a commitment to an open table, to communal meals throughout the year, would restore hospitality to the heart of Christian practice. Indeed, it is not easy to invite someone to a service of worship; but it is easy to invite them to a meal—to invite them into a sacred rhythm. When we share our lives and our stories around the table, or even around the barbeque, we break out of secular time. Our lives can take on an expansiveness, a fullness. The future can open us for us: what seemed impossible or intractable suddenly becomes manageable. We break out of secular loneliness, the loneliness of the city: around the table we can encounter human beings in depth. See, Christ is in our midst!

Is this sort of sharing not near to the heart of God? And, indeed, as Thomas Aquinas would have said—it is of the essence of God, for God is communion, communicatio (koinoinia). God is love.

In the feast, God can become possible again, even for secular people.

But God is also in the fast.  The reformers recommended 108 fasts, to be observed for a part or full-day, at each’s discretion. And here I think the Oxford Movement still has much to say to us and, in particular, Edward Pusey’s Tract 18 on fasting. Pusey’s concern was to restore what he called the “ancient discipline of the Church”—that cycle of festivals and fasts, which, he said, formed one harmonious whole of Christian humility and Christian joy.

The reformers recommended 108 fasts, to be observed for a part or full-day, at each’s discretion. And here I think the Oxford Movement still has much to say to us and, in particular, Edward Pusey’s Tract 18 on fasting. Pusey’s concern was to restore what he called the “ancient discipline of the Church”—that cycle of festivals and fasts, which, he said, formed one harmonious whole of Christian humility and Christian joy.

Fasting, he says, was anciently adopted in “periods of ease, of temptation, of luxury, of self satisfaction, of growing corruption”—in times, it seems, much like ours. The emptiness of the fast, he says, enables us to go within ourselves, to examine ourselves, and to reorientate our desires. That is how we become capable of prayer, breaking out of the maddening busyness of ordinary time. Listen to these words, written in 1833:

“In the present day, the first paramount evil which destroys its tens of thousands, is probably self-indulgence; the second, which hinders thousands in their progress heavenwards, is the being “busy and careful about many things,” … . “We have kept the vineyards of our mother’s children, but our own vineyards have we not kept.” The tendency of the age is to activity, and we have caught its spirit; if we be but active about our Master’s calling we deem ourselves secure; … Meanwhile an activity, which leads us not inwards, has taken place of that tranquil retiring meditation on the things of the unseen world which formed the deep, absorbing, contemplative, piety of our forefathers; … Our age is in general too busy, too active, for deep and continued self-observation, or for thoughtful communion with our God.

[Braced and strung by retirement into ourselves, and tranquil meditation upon God, we should return to our active duties with so much more efficiency, as we ourselves had become holier, humbler, calmer, more abstracted from ourselves, more habituated to refer all things to God.]

Moreover, says Pusey, in the emptiness of the fast we deepen our capacity for one another. We remember our dependency on one another; we remember that our life and death is with our neighbour. So we become capable of charity, of friendship. All the more will we return to the joy of table-fellowship.

He cites these words from the sixteenth century Homily on Fasting:

“God that hath promised to turn to us, if we refuse not to turn to him: yea, if we turn our evil works from before his eyes, cease to do evil, learn to do well, seek to do right, relieve the oppressed, be a right judge to the fatherless, defend the widow, break our bread to the hungry, bring the poor that wander into our house, clothe the naked, and despise not our brother which is our own flesh; Then shall thou call, saith the prophet, and the Lord shall answer; thou shalt cry, and he shall say Here am I” (Homily on Fasting 2).[1]

This is the spirit of the fast.

3.

Yes, it is by observing a sacred rhythm that God can become possible even for secular people. For God is in the rhythm of fullness and emptiness. God is in the rhythm of sharing and solitude, of feasting and fasting. In a world grown lonely, God is in the fullness; and in a world grown fat with luxuries, God is in the emptiness. God is in the rhythm, as the cantus firmus of life—as the bass note which carries all.

Let us live this sacred rhythm, in company with others! So we will break out of secular time, with its busyness and its demands. We shall hallow the time, marking our citizenship of another kingdom.

Charles Taylor ends his work, A Secular Age, with this prediction of religious revival—precisely because the grind of secular time is simply too hard:

He says: “this heavy concentration of the atmosphere of immanence will intensify a sense of living in a ‘waste land’ for subsequent generations, and many young people will begin again to explore beyond the boundaries” (p. 770).

“And in ways that they never could have anticipated, some will begin to wonder if “renunciation” isn’t the way to wholeness, and that freedom might be found in the gift of constraint, and that the strange rituals of Christian worship are the answer to their most human aspirations, as if, for their whole lives, they’ve been waiting for Saint Francis.”

It is the Church’s responsibility to offer them a way. So may it be. Amen.

[1] [Finally, Pusey commended fasting as a form of public protest against the materialism of the world and the corruption of the Church. He says inter alia, “the Church and the world are too much amalgamated …. while the light of the Church has in part penetrated the gross darkness of the world, there is yet danger, lest that light itself should be obscured. Yet the remedy for this, under God’s blessing, is not to be sought in rescuing or concentrating some scattered rays of that Church, while the Church itself is abandoned to the world. The Ordinances of the Church itself afford the means of its own restoration.]