Corpus Christi

1.

This week the Church marked the feast of Corpus Christi, the feast of the Body and Blood of our Lord–on 15 June–the axis of the year. This is one of the two great Eucharistic days in the calendar. The other is Maundy Thursday in Holy Week, when we remember Christ’s institution of the Eucharist on the night before he was handed over. That is a fast—a sad, solemn day. But Corpus Christi is a feast, a day of gladness.

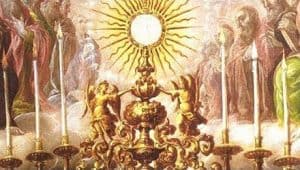

I remember the first time I saw the liturgy for this day. The priest carried the host around the Church in a monstrance, a great ornamental case of gold, which looked like a starburst or a sun. We all sang Tantum Ergo, the hymn of St Thomas (in English!). And I did feel, actually, the presence of Christ radiating there and swelling in waves of peace. It was as if God was soaking into us. I came out feeling reenchanted; I was happy to be with the faithful people there and to share in the gentle conversations one has after Church. Community life was taking shape again, even here, with these people, many of whom were little more than strangers—all, no doubt, carrying their own wounds and heaviness. But Christ had come near, a healer, to bind us together.

I remember the first time I saw the liturgy for this day. The priest carried the host around the Church in a monstrance, a great ornamental case of gold, which looked like a starburst or a sun. We all sang Tantum Ergo, the hymn of St Thomas (in English!). And I did feel, actually, the presence of Christ radiating there and swelling in waves of peace. It was as if God was soaking into us. I came out feeling reenchanted; I was happy to be with the faithful people there and to share in the gentle conversations one has after Church. Community life was taking shape again, even here, with these people, many of whom were little more than strangers—all, no doubt, carrying their own wounds and heaviness. But Christ had come near, a healer, to bind us together.

I know of course that this sort of ritualism has never been fully accepted in Anglican circles—but there it is, my own deeply felt reaction. Let the old disputes stay in the past, I say; Corpus Christi meant so much to me because it was a kind of social miracle, quelling, for a time, the harshness and loneliness of the city. Christ had come near as a humanising presence.

And that is what the Eucharist is all about. Christ is present in the midst of the people. Christ is present, bestowing his blessing. Christ is present as the food and drink of our common life.

2.

Christ is present, building up the new society. The Body of Christ is knitted together on earth, and we ourselves are his hands and his feet. Christ is our social bond, or perhaps our soul. This is the meaning of Corpus Christi; it is the meaning of Eucharist, the great social sacrament.

In fact, in medieval Europe Corpus Christi was a major summer holiday—a feast of universal charity, a feast of friendship. On this day everyone, whatever their social status, became equals, for all are equal in Christ. And in the spirit of carnival, peasants would even play at being kings for a day. It was a day for suspending competition and rivalry.

I wonder, maybe the spirit of this feast was something like our Australian summer Christmas. We know, don’t we, how after all the anxiety and competition of the year, we can settle down with friends on that great holiday to share our stories, and laugh a little. Things start to seem possible again. The world really is enchanted: Christ is present. This is how life should be all the time, we think.

I wonder, maybe the spirit of this feast was something like our Australian summer Christmas. We know, don’t we, how after all the anxiety and competition of the year, we can settle down with friends on that great holiday to share our stories, and laugh a little. Things start to seem possible again. The world really is enchanted: Christ is present. This is how life should be all the time, we think.

The spirit of Corpus Christi did continue all year in an interesting social institution—the medieval fraternity. The heart of the fraternity was regular celebratory meals, involving people from all walks of life. Here rivalry was suspended; heirarchy was levelled. The way to succeed here was to become skilled at giving and receiving respect, across boundaries. People came to see that, whatever their differences, they were fundamentally one in Christ. (QV Rowan Williams’ Lost Icons: Reflections on Cultural Bereavement, Chapter 2 “Charity”.)

The fraternity also organised liturgy and pastoral care. But let’s notice that the way into the worshipping life of the church was, first of all, getting together around the table. This sort of table-fellowship inevitably points to the Eucharist: it points to Christ, who is himself the food and drink of our common life.

So I wonder, could we in the twenty-first century revive the practice of communal meals as a way into worship? It is worth pondering.

3.

I do know that our society desperately needs a place for charity and friendship, for socialising our children, for respectful greeting, for story-telling, for remembering, for understanding across boundaries: there are precious few places for this sort of activity. As it is, people get together maybe via social media or the pub.

In a society geared to activity and production, where can we take our rest? Certainly we no longer keep the feasts of the church: we have lost that sacred rhythm.

As secularism shows itself to be so emotionally unsatisfying, the Church has a great opportunity. For here, Christ is present as our social bond. This is my body given for you. This is my blood of the new covenant, shed for you and for many. These are transforming words, words to heal many divisions and wounds.

And what does St Paul say? “For just as the body is one and has many members, and all the members of the body, though many, are one body, so it is with Christ. For in the one Spirit we were all baptized into one body–Jews or Greeks, slaves or free–and we were all made to drink of one Spirit. … As it is, there are many members, yet one body. The eye cannot say to the hand, “I have no need of you,” nor again the head to the feet, “I have no need of you.”… God has so arranged the body, giving the greater honour to the inferior member, that there be no dissension in the body, but the members may have the same care for one another. If one member suffers, all suffer together with it; if one member is honoured, all rejoice together with it. Now you are the body of Christ … .”

The great words of St Paul in the 12th chapter of his letter to the Corinthians.

This is the spirit of Corpus Christi. This is the spirit of the Church.

May we find new and creative ways to speak about this reality–the Christ, who is in our midst, drawing us all together as one.

Amen.