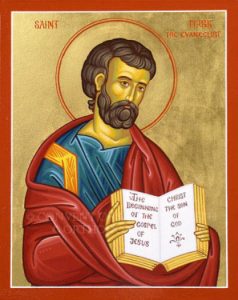

Mark

Now we begin again: now in Advent, the beginning of the Church’s year, we come to the Gospel of Mark—Mark chapter 1, which begins “The Gospel of Jesus Christ, Son of God.”

So perhaps I will share some of my reflections on this Gospel, so unlike modern literature. It might even seem barbarous and unpolished to those who approach it like a novel. But I love it. It is elusive. It is terse, finely crafted, full of subtleties, full of secrets.

One example: consider the author’s observation that, at the feeding of the 5000 by the Sea of Galilee, the grass was green. Why does the author say something so inconsequential? Because in Psalm 23 we hear “the Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want; he shall feed me in a green pasture, and lead me forth beside still waters…”

So much for the gospel’s subtlety. What I first want to notice is that the gospel of Mark’s Jesus is about forgiveness. That had been the Baptist’s proclamation too. And in this text to forgive means literally to unbind.

What I think we need to talk about is Jesus’ ministry of binding and unbinding.

For Jesus, we hear, binds the Strong Man; he binds Satan and all the demonic powers, and plunders his house. He binds the forces of disturbance in the world. But how?

When Jesus encounters a demon at the meeting house in Capernaum he says, “we know who you are, the Holy One of God!” He shouts back, “Keep silence!”

Jesus, likewise, speaks silence to the seas that rage with a demonic force. Keep silence! he shouts to the waves: in fact, the word in Greek means “be muzzled!” To muzzle something is, of course, to bind it in silence.

Jesus binds Satan in silence.

In Mark’s gospel Satan and the ‘demonic powers’ especially work through language to whip up disturbance: it is our conventional ways of speaking that keep us unwell: for we internalise accusation, and we allow ourselves to be defined by our sins. Remember, Satan is the Accuser and the Adversary—that’s the tradition we have from Job. And to bind Satan means to silence the voice of accusation, the voice of affliction.

It means, oftentimes, to remove ourselves from conventional ways of speaking. Notice that every healing and exorcism in Mark involves Jesus’ taking someone apart—away from the crowd, outside the village, to a faraway place. They go outside custom and convention, outside ordinary ways of speaking, of seeing. Only then can the Satanic voice of accusation be hushed; a situation can be spoken differently. Then there is unbinding; there is forgiveness.

So you see, forgiveness in Mark is lifting the burden of accusation. And here in Mark we see an observation almost psychoanalytic: disturbance, neurosis, illness, work linguistically: but if, in quietness and stillness, we can speak a situation differently, someone has a chance to become well. If we clear away the internalised voice of accusation, which marginalises and shames, then their eyes and ears are opened; they become open to God the Holy Spirit, who empowers them.

All of Jesus’ healings and exorcisms have this pattern: we must go apart, away from the conventional speaking which would define us. Sometimes the text insinuates this quite subtly: for instance, when he finds a little girl, aged 12, lying in bed, apparently dying, he first throws out the weeping and wailing crowd. Then before God, he is able to speak the situation differently: she is only sleeping. Jesus speaks a holy word into the situation, interrupting conventional seeing, conventional speaking. She is only sleeping. So he binds Satan, and unbinds the girl: she is healed.

Much more could be said.

Let us notice that, in Mark, Jesus is not only a prophet of forgiveness, but also of human solidarity.

At the heart of this gospel are the feeding narratives–the first to the Jews and the second to the Gentiles—both in faraway places, outside the walls, so to speak where the nature of their humanity can be spoken differently.

Jesus feeds the Jewish crowd by the shores of Lake Galilee with 5 loav es, and the Gentiles near Roman Decapolis with 7 loaves. [The fish were a later interpolation: CT]

es, and the Gentiles near Roman Decapolis with 7 loaves. [The fish were a later interpolation: CT]

There is significance in the numbers. You will notice that 5 and 7 add up to 12. Jesus feeds all the nations with 12 loaves. But what is the meaning of this twelve? It is a meaning lost on the disciples : Jesus even goads them about it in the boat on the lake: do you have eyes and not see, ears and not hear? The text says “their hearts were hardened, for they did not understand about the loaves.” Indeed not. It is a theme scholars have called “bread obtuseness,” but perhaps many scholars have not eyes to see.

What is the meaning of these twelve loaves? I was always struck by the fact that, in the Temple at Jerusalem, there were twelve loaves arrayed on a golden table, the Shewbread, or Bread of the Presence—to symbolise the bounty of God upon God’s people Israel, yes, all twelve tribes. Now Jesus breaks bread in the sight of all. Surely it is a political act: for he says, now the Temple goes out into all the world, among people of every tribe and language and nation.

So where is God if not in Jerusalem? God is with all who have trust: the seed of God takes root in their heart, too, growing up by night—even if perhaps they are strange or foreign or impure. God reigns in their hearts, so they need no longer be ashamed or defined by accusation. That is their healing.

This is, I think, something of the mystical heart of Mark.

It is a gospel full of secrets. And, of course, not everyone would see it quite as I do.

For now let us remember the greatness of Mark’s Jesus, a prophet of forgiveness and of human solidarity, much like the Baptist himself.

May they go before us always.

Amen.