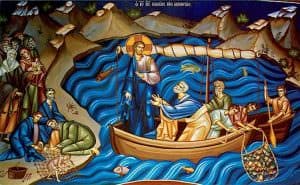

Fishing

“Again, the kingdom of heaven is like unto a net, that was cast into the sea, and gathered of every kind: Which, when it was full, they drew to shore, and sat down, and gathered the good into vessels, but cast the bad away.

Ned Flanders’ Jesus fish – Simpsons

The kingdom of heaven is like a net—a net to catch people out of every nation.

I am in the habit of going to an interesting compilation of references from the early theologians of the Church, which was put together in the theological renaissance of the thirteenth century. It is called the Golden Chain, Catena Aurea: there I found a wonderful quote from Pope Gregory the Great, in the sixth century, about the similitude of the net. He says:

“The Holy Church is likened to a net, because it is given into the hands of fishers, and by it each man is drawn into the heavenly kingdom out of the waves of this present world, that he should not be drowned in the deeps of eternal death. This net gathers every kind of fish, because the wise and the foolish, the free and the slave, the rich and the poor, the strong and the weak, all respond to the call of mercy [that is, the forgiveness of their sins]; it is then fully filled when in the end of all things the sum of humanity is completed.”

This net catches all people, for all are drawn to the call of mercy, to the forgiveness of sins. So it is that the Church offers an unconditional welcome to all, a non-judgmental acceptance of human beings—whatever their history, whoever they have been in the past. This is not some trendy, modern-day attitude, but it has always been of the essence of the Church. There is a fundamental equality in the kingdom. All are, in the words of scripture, justified. What does that mean? It means we are declared just and made just (cf Hans Küng, Justification). We are freed from accusation. We are restored. Those who have been cut off return to the fold. Our sins are forgiven.

Just as the net catches fish of all kinds, so all who have trust in God are justified. It is a point we hear in elsewhere, too: remember the labourers in the vineyard—all of them are paid precisely the same amount, whatever they have achieved. They all receive the coin of mercy, whatever their accomplishments in before times. Remember the wedding banquet, to which everyone is invited—the poor, the lame, the crippled, the blind. All are welcome.

Furthermore, this was, it seems to me, just what was recovered at the reformation—the gospel of mercy, the gospel of a gracious God, a compassionate God who bears with human error and forgives sins. This was the God of Martin Luther; indeed, the great reformation sense of the equality of all human beings under God has been like a great river flowing through the centuries right into the present.

Maybe the genius of the reformation was to recover a sense of the goodness of ordinary people, if they are freedom from accusation and judgement.

Yet, I wonder, is this the whole story? No, I think not. I read before the words of Gregory the Great: but that wasn’t the end of his reflection; it continues like this: [the net]

“…when it was filled, they drew out, and sitting down on the shore gathered the good into vessels, but the bad they cast away.” For as the sea signifies the world, so the sea shore signifies the end of the age; and as the good are gathered into vessels, but the bad cast away, so each man is received into eternal abodes, while the reprobate, having lost the light of the inward kingdom, are cast forth into outer darkness. For now the net of faith holds good and bad mingled together in one; but the shore shall discover what the net of the Church has brought to land.

Yes, all have been welcomed into the Church, with full amnesty and acceptance, whoever we are: there is a fundamental equality in that sense. Yet we shall still be judged on the basis of what we do with our freedom. And here I think the reformation emphasis needs balancing out. We will not, indeed, be judged according to the old law of Israel—not by works of that law: no, we will be judged by a new standard (cf Mt 25). How well have we treated our bothers and sisters? How have we served humanity? This is the measuring line in the new covenant. We are judged according to how we treat our brothers and sisters.

Therefore even in the kingdom of heaven there is a certain hierarchy. But it is an inverted hierarchy, an upside-down order: it is nothing like the hierarchy of the world, based on money or power. No, the greatest are they who serve their brothers and sisters, losing themselves for the sake of the other. It is they who have achieved the purpose of the old law—the end (telos) of the law. It is they who are lighted up by the righteousness of God.

Therefore even in the kingdom of heaven there is a certain hierarchy. But it is an inverted hierarchy, an upside-down order: it is nothing like the hierarchy of the world, based on money or power. No, the greatest are they who serve their brothers and sisters, losing themselves for the sake of the other. It is they who have achieved the purpose of the old law—the end (telos) of the law. It is they who are lighted up by the righteousness of God.

Maybe we feel we are not very good at serving humanity. Most of us are not saints; yet Matthew tells us that all will receive a reward, all except those who yield no return at all. They are like the fearful servant who buries his coins in the earth. They make no return on what God has given them. And, as we hear, they are like the bad fish, or maybe the urchins or sea-snakes, which are cast away.

We are accepted, forgiven and fundamentally equal in Christ, whoever we are; but, there is also the potential for growth and degree in the way of love. Indeed, it is just because we are treated with real dignity in Christ that we are enabled to grow. And this is, it seems to me, our catholic inheritance: as Aquinas might have said, the spiritual journey is an ascent—we rise higher according to how skilful we become at friendship, at charity.

It seems we need both perspectives, the horizontal and the vertical, if we are to understand what our salvation means. The kingdom, like a net, catches every kind of fish; yet at the end of the age they will be sorted one from another. So, may we who have been caught rededicate ourselves to serving humanity.

Amen.