Human Being, Martyr

… in Christ God was reconciling the world to himself, not counting their trespasses against them, and entrusting the message of reconciliation to us. (2 Cor 5)

In his second letter to the Corinthians Paul reflects again on the atonement—a reflection obscure, it seems, as ever to us. I must admit some fear venturing on a topic like this. How can we make sense of it at all?

I don’t have a final answer; but perhaps I have one or two thoughts, or notes towards a solution. Bear in mind that the Church never laid down one, authoritative way to understand Jesus’ death.

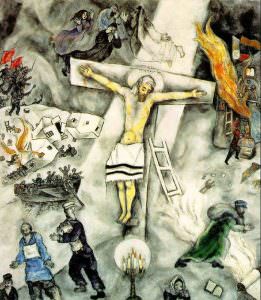

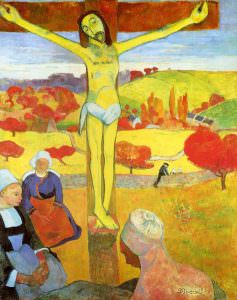

For some time I’ve been thinking of Jesus’ death as a martyrdom: a word which, I think, brings together so many threads. A martyr is a righteous one who does not waver even to death and who, by his death, shakes the world. A martyr overcomes evil not by strength of arms, not by violence, but by the force of truth—a truth which he or she even embodies. And in this self-sacrificial act, the truth shines forth. To be sure, the martyr pays a high price–a pound of flesh to the devil, if you like: yet he clears a space for the appearing of God. God and humanity somehow come together.

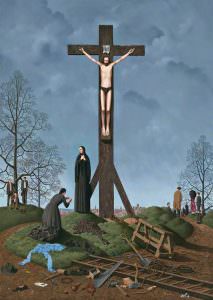

Isn’t that what the cross is all about? Perhaps we aren’t used to hearing of it like this. Yet I think it accords very well with the ancient proclamation of the Church that, though he was put to death, Christ triumphed over the powers of evil. His death somehow overthrew the powers and rulers of this world, maybe even something like a judo throw (qv Shanks An Honest Church: Anglicanism Reimagined). The powers of darkness were overcome; a new age began. Christ was victorious. As the Swedish Bishop Gustav Aulén reminded us in 1930, the authentic proclamation of the early Church was Christus Victor!

Christ’s death witnesses against the lawless powers of the world: but what powers are these? See how Christ dies. It is a catastrophe of lawlessness. Peter is sorely tempted to bear false witness: They accuse him, you are a Nazarene, but he denies it. He denies it three times, before weeping bitter tears of repentance. The supposed guardians of righteousness sit in the Sanhedrin, yet in our accounts they bear false witness. Many witnesses came forward, but their testimony did not agree. And even more subtly, the High Priest tears his garment, though it was unlawful to desecrate the sacred robes (at least on one understanding of Lev 10:6).

Through it all, Jesus keeps silent, refusing to be bound by their accusations, refusing to be judged by their authority.

“He was oppressed, and he was afflicted, yet he did not open his mouth; like a lamb that is led to the slaughter, and like a sheep that before its shearers is silent, so he did not open his mouth. By a perversion of justice he was taken away.” (Isa:53)

So says the prophet Isaiah. The righteous one goes as a martyr. He is the “righteous one, God’s servant”–but they do not know it. He is like the scapegoat on the day of Atonement (Yom Kippur), bearing the sins of many. He does not repay violence with violence; he is the man of non-violence. Therefore God vindicates this one: “I will alot him a portion with the great” says the prophet Isaiah. The martyr triumphs by the force of his own truth.

So says the prophet Isaiah. The righteous one goes as a martyr. He is the “righteous one, God’s servant”–but they do not know it. He is like the scapegoat on the day of Atonement (Yom Kippur), bearing the sins of many. He does not repay violence with violence; he is the man of non-violence. Therefore God vindicates this one: “I will alot him a portion with the great” says the prophet Isaiah. The martyr triumphs by the force of his own truth.

A martyrdom is a social commentary. So it is with Christ’s death. Israel had the law of God, yet lawlessness abounded. The commandments could not restrain it. More than that, mutual accusation multiplied. Now, in a supreme irony, the Righteous One himself stands condemned: that is the earth-shattering Christian proclamation—relevant to every age, it seems, where law abounds, threatening our humanity—where law abounds, obscuring the face of God.

Yet here is God, working hiddenly. God makes a way out for us—a new exodus, a new Passover. God in God’s mercy does not count our former sins against us or else, we feel, we should be obliterated—such was our lawlessness. Yet one human being has been found righteous, and that is enough.

What is the way out of this oppressive social situation?

It is to become one with Christ in his death and resurrection. St Paul speaks of this as a rising up. We die to lawlessness—to our selfish and violent and retributive self, which he calls “the flesh”; and we rise into the spirit, the new humanity. We leave behind guilt and accusation. We come into a new community, living not for ourselves but for one another. It is a new, reconciled humanity.

No longer do we need law to restrain us, for we have undergone an inner transformation. Now we live for another: we have Christ. We live into the universal person. We go into the heart of humanity.

As our text has it, “One died for all, therefore all died….in Christ God was reconciling the world to himself, not counting their trespasses against them, and entrusting the message of reconciliation to us. ”

That is my understanding of Jesus’ death. And the most potent way I know of explaining it in the contemporary situation is to say that Christ dies a martyr—the great Martyr, the Righteous One. Human Being, Martyr. When we stand with this powerless one against the powers of the world, we are strong—for we stand in the truth. Even in the violent and barbarous world, we clear a place for the appearing of God.

Now let us remember the Eucharist, the feast of Christ’s body and blood—the mystery of our union with Christ in his death and resurrection. May we draw ever nearer to Christ, who is in our midst.

Amen