Jesus of the Poor

“The Son of Man came eating and drinking, and they called him a glutton and a drunkard, a friend of tax-collectors and sinners,” Mt 13

1.

I must admit I’m fond of this line, mainly because it makes Jesus seem the life of the party—much more fun than his more puritanical followers might like to admit. In fact we hear the accusation that Jesus is overindulging in food and wine just after he returns from the house of Matthew, a tax collector. Tax collectors were in especially low regard because they were agents of the Roman Government in occupied Judea. Nevertheless, Jesus went down to Matthew’s house to recline with crooks and bounders and thieves, splashing around new wine!

I must admit I’m fond of this line, mainly because it makes Jesus seem the life of the party—much more fun than his more puritanical followers might like to admit. In fact we hear the accusation that Jesus is overindulging in food and wine just after he returns from the house of Matthew, a tax collector. Tax collectors were in especially low regard because they were agents of the Roman Government in occupied Judea. Nevertheless, Jesus went down to Matthew’s house to recline with crooks and bounders and thieves, splashing around new wine!

The Son of Man eludes every expectation. He comes not as a cold moralist, but as a lover of life, a lover of human beings. He asks us not to be perfect (despite that unhappy translation in Matthew’s gospel) but complete or, even, great-souled (teleios) – bringing in the righteous and the unrighteous alike, bringing in the evil and the good. He eats with tax collectors and sinners. He teaches us to rely completely on the mercy of God, and ourselves to be merciful. I desire mercy, not sacrifice, he says.

What is this but a gospel of restoration? A gospel of home-coming for sinners, a gospel of restorative justice for all who have trust in God?

This is the Jesus who angers the Pharisees. It is the Jesus of whom many Christians have yet to learn–Jesus the restorer of the breach, the bringer of mercy.

2.

Maybe we like to think that this gospel is not relevant to us. We do not live in a moralistic culture: we don’t usually denounce people as sinners these days. We are free to live our lives as we wish.

But I wonder, are we really so free? In fact much of what the ancients called sin we now call crime. More and more we live in a highly policed society, a society abounding in legislative solutions to social problems. More human conduct is criminalised now than at any time in history. In the United States, I understand, the prison population is near to 2 million people. And what about trial by media? Or the erosion of the ancient principle of English law that you are innocent until proven guilty? Or the abundance of surveillance: there are cameras on every street corner.

Doesn’t all this suggest that our social bond is badly frayed?

More and more we do not relate to one another as human beings, spending time, taking time, sharing our lives and our stories. There is a real decline in trust and goodwill.

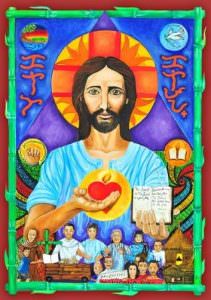

And yet, Jesus comes among us as the restorer of the breach. He arises in our midst one like a Son of Humanity. Jesus comes to restore the social bond, the bond of trust between people. He comes to preach the radical idea that the worship of God implies hospitality and table-fellowship. For when we turn to God in trust, we turn in trust to our brothers and sisters. We strive to see all the world in the light and warmth of the sun – the sun who is God. See, there is the Holy One in our midst! Yes, even sinners find a place at the table, if they are capable of trust: for this is the basis of all friendship and virtue.

3.

This is the Jesus who is too little known, the Jesus unknown to fire and brimstone street preachers and puritans alike – Jesus, the restorer of the breach, the bringer of mercy, friend of tax collectors and sinners.

This is the Jesus who is too little known, the Jesus unknown to fire and brimstone street preachers and puritans alike – Jesus, the restorer of the breach, the bringer of mercy, friend of tax collectors and sinners.

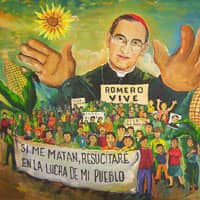

Sometimes I wonder: are there two gospels, the gospel of restoration and the gospel of mere moralism? This thought came to me forcibly when lately I read Pope Francis’ 2013 pastoral exhortation The Joy of the Gospel, which is important for Anglicans too (q.v Paula Gooder’s 2015 Anglican study guide to this letter). There he announces his wish for a church for the poor—not only for the materially poor but the spiritually poor, too. We are called to accompany the poor, to make possible for them lives of growth and meaning. We are called to be a merciful people.

Francis says:

“Moved by [Jesus’] example, we want to enter fully into the fabric of society, sharing the lives of all, listening to their concerns, helping them materially and spiritually in their needs, rejoicing with those who rejoice, weeping with those who weep; arm in arm with others, we are committed to building a new world. But we do so not from a sense of obligation, not as a burdensome duty, but as the result of a personal decision which brings us joy and gives meaning to our lives.”

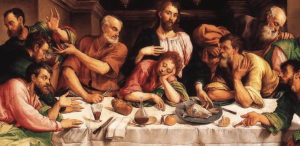

And at the heart of our life is a common meal. In this context Francis says “the Eucharist is not a prize for the perfect, but a powerful medicine and nourishment for the weak.” We come to this banquet: we come to the feast of our restoration. Here Jesus feeds us with his very life, and the social bond is renewed; the life of the community, frayed and broken as it is, comes together again. No matter how bad things get in the wider world, Jesus is always appearing in our midst, a mystical presence at the heart of society.

The question is, do we recognise him? Do we have eyes to see? Or are we like the Pharisees, who dismissed Jesus as “a glutton and a drunkard, a friend of tax collectors and sinners.”?

May we always have eyes to see this Son of Humanity, this Human One.

Amen.