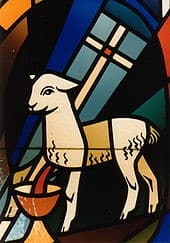

The Lamb of God

The day after Jesus has been baptised by John the Baptist, we hear John proclaim: “Behold, the Lamb of God!” and, at this point I would argue, the church is granted for all time one of the most powerful images of our Lord: “The Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world.” So powerful and enduring is this image that you will find it clearly evident in our Eucharistic theology and liturgy. Rightfully so I contend.

In the Revelation to John (‘Revelations’) we read the same phrase, but there ‘the Lamb of God’ is repeated numerous times. However, we are confronted with metaphorical usage that does not always make sense. Initially we hear of ‘lamb to be slain’ [chap 5:6], ‘the lamb that stands on Mount Zion with his followers’ [14.1]. But then we also read in 7:17 that ‘the Lamb at the centre of the throne will be their shepherd’ (odd, we say, usually it is the other way around) and in 13:8 we learn that the Lamb keeps a ‘book of life’ in which the names of the faithful are inscribed. In chaps 5 and 6 we learn of the Lamb opening the seals of destiny. These latter activities are not usually associated (metaphorically or literally) with lambs.

One might simply conclude that this is a type of poetic license taken by the author of Revelations or, more likely, that the author has made a simple and reasonable assumption: ‘The Lamb’ = ‘the Messiah’ and, since his readership would have known this, no explanation is necessary. Furthermore, there are real efforts made in Revelations to reinforce the idea of ‘the Lamb’ in apocalyptic themes. In the new heavenly Jerusalem, the city is the bride of the Lamb [21:25] and the Lamb serves as temple and light within the city. This Lamb/Messiah figure is referred to so frequently that we can’t cover all these references here.

So let me now explain why I jumped from the single reference to ‘The Lamb of God’ in John’s Gospel to the many reference to ‘the Lamb’ in Revelations: it is because the phrase ‘the Lamb of God’ – truly significant words uttered by John the Baptist in the first chapter of John’s Gospel – means so much more than we usually attribute to it. Admittedly, by far and away the most popular understanding of ‘the Lamb’ is that it is a reference to the Passover (Pascal) lamb [Ex 12]. The feast from ancient Old Testament cultic practice that once a year required the sacrifice of a lamb to commemorate that ‘passing over’ of the angel of death (because the blood of a one year old lamb had been daubed on the door lintel and frame.) Surely this is the lamb to which John the Baptist was referring?

But there is a slight problem here: As the Westminster Bible Companion commentary on John points out:

“John’s words in v. 29 (“Here is the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world”) are well-known to many Christians, but not in this context. They form part of many eucharistic liturgies, spoken at the breaking of the bread. Jewish worship practices, however, not later Christian practices, provide the background for understanding John’s words here… Christians assume that the words “lamb of God” point to Jesus as a sacrifice offered for the purification of sin. But in Jewish temple practices, a bull, a sheep, or a goat (see Lev. 4-5), not a lamb, was the animal offered for a sin sacrifice. The lamb is the animal offered at Passover, and the Passover lamb is not offered as a sacrifice for sin but to commemorate Israel’s deliverance from slavery in Egypt (see Exod. 12:1-13). John the Baptist is not pointing to Jesus as a sacrifice for human sins but as a symbol of deliverance and liberation.

And as we have seen, Revelations explores and expands this symbolism in some depth.

But what is not required here is a hasty rewrite of our eucharistic liturgy, hurriedly shifting our language from sacrificial to the powerful (apocalyptic) lamb revealed to us in Revelations. Just reading 1 Corinthians 5:7 “[f]or our pascal lamb, Christ, has been sacrificed,” and 1 Peter 1:18f “You know that you were ransomed [w]ith the precious blood of Christ, like that of a lamb without defect of blemish,” illustrates that both these authors were content to utilise the ‘pascal lamb’ imagery in understanding the work on the cross.

What may ultimately help us here is a chronology. I Corinthians dates from c 54 and, I Peter (the date of which is contested) as late as 81. John’s Gospel, it is argued by C.K. Barrett, may have been written as late as c100. Observing this chronology and the necessary evolution that took place in the thinking of the first century church, perhaps the words of C.K. Barrett should be given the right of final say: “John the Baptist, or at any rate the earliest Christians, thought of the Messiah as the apocalyptic lamb, destined to overthrow evil. But Christian theology pondered the fact of Jesus’ death, and Christian liturgy developed the notion of the Christian passover. John the Evangelist brought the resultant wealth of material together in a term which, like many that he used, was at once Jewish and Hellenistic, apocalyptic, theological and liturgical ; and so deposited at the centre of Christian theology, liturgy and art the picture of the agnus dei qui tollit peccata mundi.” (Short Studies, The Lamb of God)

John the Baptist, in John’s Gospel weaves together the broadest possible understanding of the Lamb of God (at least, the breadth of the first century.) This must be our understanding too.